Promulgate. Depending on the kind of person you are, the word may not be simple to spell. A quick search in the Merriam-Webster dictionary will return promulgate’s definition as this: to make known to many people by open declaration. Nobody sane is going through their day using promulgate. “I really want to promulgate how I’m feeling right now.” Definitely not. The majority of the words used during the Scripps National Spelling Bee aren’t the ones you or I or anyone would mix into their everyday vocabulary. They’re words collected from the deepest crevices of the English language, strung together with intricate elements—prefixes, suffixes, hidden consonants and vowels, an absurd number of syllables—all seldom used in conversation and seemingly reserved solely for use during the National Spelling Bee. And there’s actually a word for a word that is long: sesquipedalian.

To many, the Scripps National Spelling Bee isn’t must-watch television. The annual competition probably comes and goes without ever being brought to people’s attention other than those who share a deep passion for spelling and grammar. So, who could blame anyone for not caring about the Bee? It’s not a sport. At the National Spelling Bee’s core, it’s more than 200 highly-gifted elementary and middle-schoolers who have subjected themselves to rigorous levels of orthographic study sheepishly walking out onto stage inside of a convention center, standing in front of a daunting audience, stricken with fear, burdened by their parent’s expectations, ready to spell the word they’re given correctly or risk becoming fodder for the competition’s ruthless path of crushing youthful dreams beneath its dictionary-driven boot.

In a way, who wouldn’t want to watch hundreds of dreams get crushed?

Not really. For the cynics out there, sure, that could very well be the case. The fact of the matter is that when the National Spelling Bee was broadcasted widely—specifically during the run the competition had on ESPN from 1994 to 2021—the Spelling Bee conjured up interest and a pseudo-cult following for the two-day event across a wide variety of audiences. The national broadcast validated viewer fascination with the intensity of a competition that many participated in at some point during elementary school, broadcasted on a channel synonymous with the most high-profile sports in North America. And that’s exactly what former bee champion and analyst for the ESPN broadcast Katie Kerwin McCrimmon told Vox in 2018:

"My first thought when they started broadcasting the Bee was, 'Why would anybody care?' ESPN seemed like such a mismatch to me, but they always said that when it went on in sports bars, people would just eat it up."

The Bee has always been compelling to watch. It hooks you in. Kids with disheveled looks, rough haircuts, braces, walking out with their hands jammed into their khakis as far as the pockets allow. There’s a semblance of both hope and fear etched into competitors’ faces, that their dreams and career aspirations lie within the correct-spelling of some niche word derived from Greek mythology. They mumble. They ask the pronouncer if they can use the word in a sentence. They drag out all two minutes and thirty seconds. And most of the time, the kids do fail. They hear the ominous ding of the deadly bell that eliminates them from a competition they’ve been training years for. And yet, on rare occasions, the broadcast of the National Spelling Bee gives audiences incredible moments of triumph; perseverance in the face of attempting to spell a brain-scrambling word.

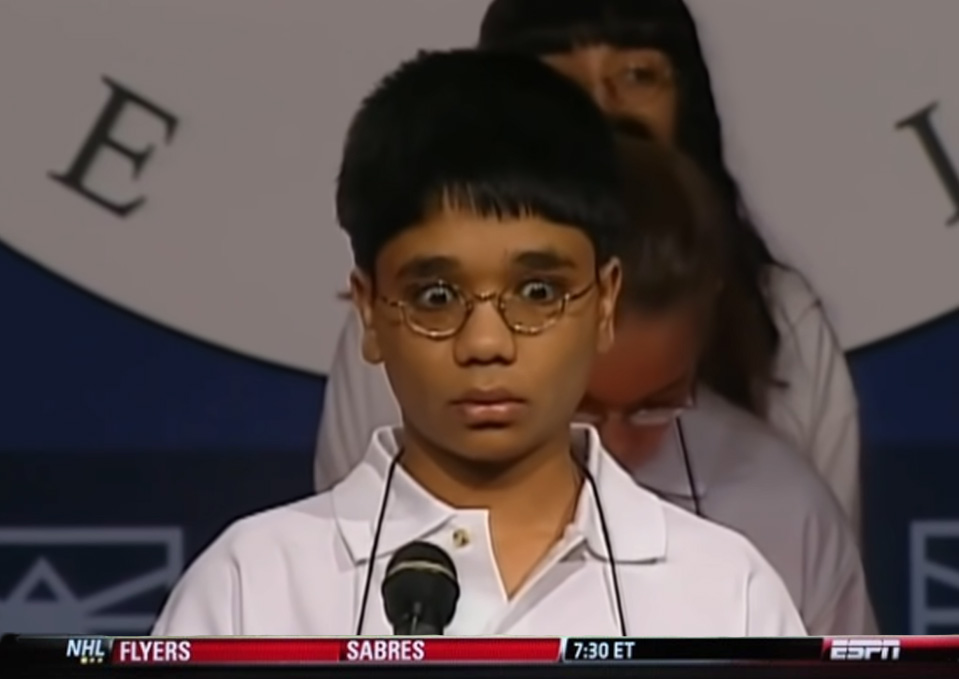

Akshay Budigga was in round six of the 2004 National Spelling Bee. Roughly 30 competitors remained. His word: alopecoid. Definition: like a fox, vulpine. Language of origin? Greek. The camera stays glued to him as his eyes flutter, head nodding forward. Akshay mumbles; asks for bonus time. The convention center is silent besides whispers from the crowd and ominous hum of feedback from the microphone. What happens next lives on as a pre-YouTube viral moment. A performance that should be lauded next to some of the gutsiest plays in sports history. It was exactly the kind of moments that made the odd relationship of ESPN and the Scripps National Spelling Bee flourish.

However, in 2022, the National Spelling Bee left ESPN airways. This was courtesy of the E.W. Scripps Company—the media conglomerate that’s been in operation since 1865 and has run the Bee since its inception in 1925—and their decision to not renew the contract with ESPN, instead bringing the competition’s broadcast to their own network, ION.

ION is the channel known mostly for their litany of reruns, daily regurgitations of shows suburban America seethes for like Law & Order, Chicago Fire, Chicago P.D., Chicago Med. But here the focus shouldn’t be on ION because ION is not to blame. ION, to explain things simply, is just one of many media and streaming platforms that is owned by Scripps Media.

When the contract with ESPN ended after the 2021 Bee, the E.W. Scripps Company chose to separate themselves and the competition from ESPN for reasons many were told would benefit larger and more diverse audiences. Scripps President and CEO Adam Symson had this to say in 2021:

"The Scripps National Spelling Bee is a beloved American treasure enjoyed by generations of participants and viewers annually. The time is right to bring the iconic competition back to broadcast television, the media platform accessible for free to nearly every American viewer across the country."

So, essentially, what Symson said is that the removal of the Bee from one of the most widely-known channels and media platforms perhaps in the world and the subsequent transplant of the competition to a niche broadcast network that a vast majority of the population has not only never watched, but also never heard of, will allow the competition to become more accessible to a wider range of audiences?

Not only was Symson’s statement void of any sort of common sense, but his decision was a clear attempt to uproot the competition’s and its competitors’ largest access to media exposure and viewership solely because Scripps was not in control of the broadcast. It seemed to be less about audiences being able to access ESPN through their own streaming services and more like a scapegoat to authorize Scripps’ own control over the broadcast. And not being in control of the broadcast means less money, and less money means, well, less profits to boast.

When Scripps took the reins in 2022, the reviews were in pretty quickly about how terrible of a broadcast the competition was, one crammed with advertisements and a complete tonal shift from the fun, sport-like broadcast that ESPN put on for 27 years. However, according to data provided by the E.W. Scripps Company, viewership increased after the transition, rising from 7.5 million in 2022 to 9.2 million in 2023. Again, this is broadcast data that’s provided from the company in control of the broadcast. Surely there’s no bias or fallacy within these numbers as online engagement has fallen and complaints have risen, because media company’s never falsify their data, never ever.

So, is this transition of broadcasts not only a disservice to the competitors, but to viewers as well? Maybe the decision was a clear effort by the E.W. Scripps Company to cloak their financial gain as an unselfish attempt to promulgate the Bee to a larger audience while seemingly assuring full control.

Removing the National Spelling Bee from a worldwide platform like ESPN shifted the competition away from a socially dynamic setting where viewers found themselves hooked onto a two-day event they otherwise would not have sought out. In the past, many became enthralled with the highs and lows of a competition as simple as a spelling bee because it was made synonymous with a network known for generating high-levels of interest. It’s called name-brand recognition, which also falls under the definition of how humans—and especially the kinds of people who have nothing better to do than watch a spelling bee—want the easiest and most accessible platform to watch these kinds of events.

More importantly, what about the children? Those pre-teen spellers who worked tirelessly and crammed their brains with thousands of words and definitions now find their moments of televised fame reduced to ION. No longer can they look back years after the Bee has taken place and reflect upon their appearance on ESPN. They could’ve been on the same channel as LeBron; shared a moment on the Top Ten with highlights from the world’s greatest athletes.

Queue: Akshay Buddiga.

As much as Akshay might’ve been wishing he wasn’t on ESPN while he fought through the word alopecoid, stumbling to his left, collapsing, sending a surge of worry throughout the crowd only to miraculously rise and spell the word without hesitation, his triumph was just as impressive as a third period comeback, a walk-off homerun, a Hail Mary hurled from the goal line. It’s a perfect example of why the Scripps National Spelling Bee and ESPN somehow bridged a perfect relationship that surprisingly lasted for 27 years, until their breakup left audiences with the shattered remains of what once was two oddly fun days every May. Through those nearly three decades of broadcasts, we were shown that a spelling bee could be captivating, a kid who may never again find himself on ESPN could have a Kobe-like performance, that our interests often heavily rely on the ease with which media and programs are accessed.

The transition of the broadcast from ESPN to the Scripps-owned network seems less like the definition of promulgate, and closer to the word ensconce, the definition: to firmly place or hide (someone or something). The competition; the competitors. In the name of growth Scripps has seemingly pilfered the National Spelling Bee, sequestering it on its own network, leaving behind those viewers who for two days in May found themselves loosely following a competition of elementary and middle schoolers who were already most likely much smarter and more likely to succeed than they ever were or will be. Casual viewership be damned.

For anyone interested, this year’s competition takes place May 29th & 30th.

Where can you watch? ION, if you want to go there.